Founded by Wilmington resident and University of North Carolina Wilmington researcher Dr. Jennifer McCall, SeaTox was formed when McCall saw a way to improve the sometimes days-long process of measuring marine toxicity levels following algal blooms.

SeaTox was originally awarded a grant of around $200,000 from the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences, half of which was designated for UNCW. In a collection of biotech grants, North Carolina Governor Pat McCrory also awarded Seatox with an additional $50,000 in grant funding as announced in a press release Dec. 3.

The current toxicity tests used by state regulatory agencies like the North Carolina Department of Environment and Natural Resources can take up to several days to produce results following an algal bloom. Those tests also do not offer targeted readings from smaller areas within the larger contaminated area. As a result, those closed areas are often larger than needed or the closures last longer than needed.

“State agencies monitor the sites and close them if there is a bloom but the problem is that any time they detect the organism they close it just to be overly cautious,” McCall said. “That is a real harm on fishermen, whose livelihoods depend on having access to these sites. So if we can develop rapid tests we could say these shellfish are poisonous but these are OK or we could use this inexpensive test to take readings more frequently.”

The four marine neurotoxins SeaTox is focusing on include two brevetoxins, saxitoxin and domoic acid. All of those toxins interfere with sodium channel openings that control the messages relayed to the nervous system and can cause shellfish conditions like paralytic, amnesic and neurotoxic shellfish poisoning.

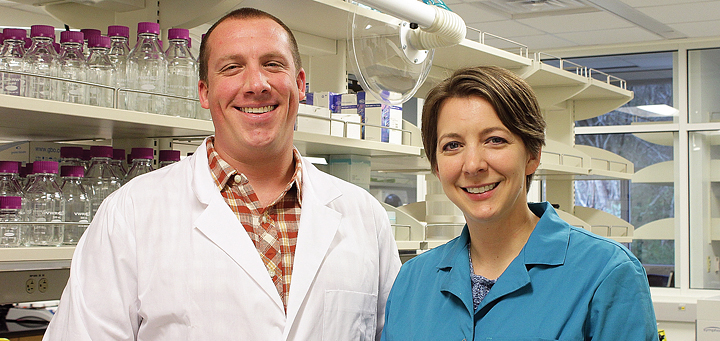

With the help of her husband, immunologist and SeaTox chief operating officer Sam McCall, McCall developed an initial test utilizing fluorescent tagging to identify the level of toxin receptor binding.

One of the reasons why a quicker, more-efficient and less-expensive test has not been developed previously is it required technology to advance to a certain point, Sam McCall said.

“Being able to take specific parts of the pathway and label them with fluorescents and develop an assay required technology to advance to a certain point,” McCall said. “We have built up a pool of science that we can use to say a certain peak at a certain time with a certain solvent means this. It just requires that pool of knowledge to build up.”

The SeaTox lab is housed in the UNCW Marine Biotechnology in North Carolina Research Park (MARBIONC) and Jennifer McCall said the community atmosphere created between the sciences at MARBIONC also helped the test develop.

“Typically when you have a lab like that you either have chemists or biologists but one of the things they are trying to do here is collaboration among the sciences and that might have been the big breakthrough,” she said. “They are really trying to go for translational science and science that can be moved in a direction to help people.”

After receiving her Ph.D. in immunology from University of North Carolina Charlotte, McCall completed her post-doctoral work at UNCW on biotechnology and received an MBA from UNCW’s Business of Biotechnology program in 2013.

Aimed to ensure more biotech discoveries and research find their ways to small businesses and end consumers, McCall said the program helped her shape the future of SeaTox .

“I do think scientists tend to be trained too much in science, which is great, but it also means a lot of interesting discoveries stay in the lab and you don’t really have that link to get it out to somewhere useful,” she said. “That would be my determination of success, that I did something that started at the bench top and became something that can help people.”